‘Education at a Glance’ – an annual report by the OECD, the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development – is also a special guide that succeeds to draw a succinct, but fool-proof summary of the state of education in countries throughout the globe.

But how should we understand ‘equity’ in the context of education? Equity in educations means learning environments built in a way to allow them to counteract the impact of external disparities, and lay down conditions where educational attainment translates more directly into equitable (satisfactory) economic and social outcomes, long after students leave school. The OECD’s report investigates whether equity has been embedded as a concept and focuses on the challenges that remain.

In a nutshell: gains in education for women overshadowed by lack of diversity in the world of work

Efforts to boost education programs so they are fit for the digital age seem to have paid off – OECD’s report finds that secondary education attainment actually improved in most OECD countries. So did labour market outcomes for young adults most at risk of lagging behind – another signifier of improved education quality.

At the same time, gains in education seem overshadowed by other less positive, yet somewhat expected trends: women worldwide continue to earn lower than their male counterparts. There is some light at the end of the tunnel though: the earnings gap does appear to be shrinking – but not that rapidly.

Yes, your gender still very much affects how much you will earn

And the figure is likely to be lower if you are a woman.

Despite scoring better result than men in education, women and girls remain at a disadvantage when it comes to the world of work. According to the report, more young women obtain advanced qualifications, for example, yet their employment rate specifically in the age group of 25 to 34, remains lower than the one of men.

The picture looks a bit better if we zoom into young adults with tertiary education: the gender gap there is smaller, but still significant at 6%.

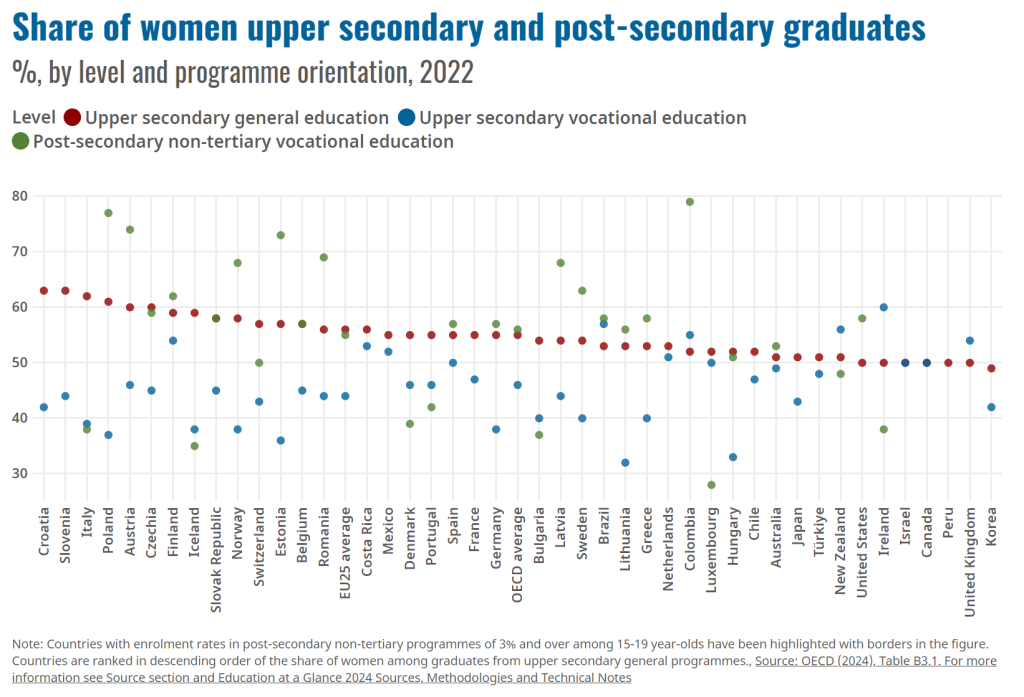

Young women also earn, on average, between 15 and 17% lower salaries and wages compared to young men. See Figure 1 below, which shows the share of women with secondary education attainment in the OECD-surveyed countries.

Powering education through STEM and ICT programs: a balancing act

Correlation but no causation for gender and education

Tertiary education is key to boosting EU-wide capacity of responding to future challenges and climate emergencies, and one of the primary ways in which the continent’s talent base with advanced ICT skills is increasing. Here, too, gender disparities threaten to overshadow overall success: women account for a much larger number of students enrolled in tertiary education, but remain underrepresented in the world of work.

More diversity in specific technology-focused subjects should also be another focus of prevailing discourse. Just 15% of women entering higher education choose a Science, Technology, Engineering or Mathematics (STEM) field – against close to half (41%) of men. Other areas traditionally taken up by women continue to suffer from low male participation: just 4% of male students went into education, and less than 8% chose health and welfare as degree subjects – a figure that according to the OECD report has remained unchanged since 2015.

Skills for jobs: responding to labour market needs

This trend is continued, if not exacerbated, in the world of work.

In nearly all of OECD-surveyed countries, young women faced significantly higher inactivity rates than their male peers, particularly amongst those without upper secondary education attainment. Foreign-born women faced a dual challenge in the labour market – first, as immigrants, and second – as women. Native-born women with tertiary education faced a gender gap in employment rates of around 5% points less compared to men on average.

Women born abroad faced a gap larger than double – a difference of over 13%.

Interestingly, OECD notes that countries with the largest share of tertiary graduates do not necessarily enjoy the highest employment rates. This brings forward yet another need – for better collaboration between academia and the labour market to 1) prevent mismatches in the supply of graduates in specific fields and 2) help to bridge specific skills gaps.

Complementary EU policymaking for skills

European funding has long attempted to address the gender gap in ICT – not just in employment, but also in society overall – by building links between academia and industry demands, allocating money for female-led business ventures, or financing public-private partnerships and actions aiming to boost the ratio of women in specialised technology areas, like Artificial Intelligence (AI), big data, or cybersecurity. The DIGITAL Europe Programme of the European Union has allocated over 8 billion for funding, with specific actions aiming to address gender disparities. It also funds specific projects like the Women TechEU call, which supports up to 130 deep-tech start-ups led by women with a budget of €10 million.

Other activities of the Commission aim to get to a safer, more secure, and resilient Europe – such as the Women4Cyber initiative, which aims to get more women interested in cybersecurity, or the Cybersecurity Skills Academy, hosted on the Digital Skills & Jobs Platform – the home for digital skills in Europe, which addresses directly the shortage of advanced, cybersecurity-focused skills in EU Member States. This is key to reaching the number of 20 million ICT experts employed in Europe by 2030, set out by the EU Digital Decade policy communication.

Education: getting to a level-playing field

Young adults outside of education

In most OECD countries, the share of 18-24 year-olds who are neither employed nor in formal education or training (NEET) has decreased between 2016 and 2023. In Europe, the only exception is Lithuania, where the OECD notes a 3% increase. At the same time, the share of young adults between the ages of 18 to 24 in education is amongst the highest in Luxembourg, the Netherlands and Slovenia (just 32% of youngsters in that age group are not in format or VET education).

Young people in vocational education & training

Amongst youngsters between the ages of 15 to 24, there is a significant overall increase in the number of people engaged in technical or vocational education programmes and training (VET). In OECD-surveyed countries, this average ratio now stands at 17%. Some EU Member States – Austria, Czechia, Poland, and Slovenia are not just leaders in Europe but also pioneers on a global scale, with over 25% of young people in some form of vocational education or training.

At the same time, challenges with uneven gender representation and engagement persist, with young men still more likely to be engaged in VET activities compared to women. Some EU countries here, though, lag behind OECD’s average by twice as much – as is the case in Italy, Norway and Poland. At the same time, a range of actions by both the Italian and Polish National Coalitions for Digital Skills and Jobs have aimed to address this discrepancy – not just in the area of VET but also across formal education and several specialised programs with a focus on diversity.

Tackling early school leaving

Recognising this, many OECD countries have lowered the starting age of compulsory education. They have also increased public expenditure on early childhood education, by 9% on average between 2015 and 2021 when measured as a share of gross domestic product (GDP). In some countries, the rise was much higher. For example, public expenditure in this area went up 50% in Lithuania and 42% in Germany. However, Education at a Glance shows that gaps remain, particularly in the affordability and accessibility of early childhood education for low-income families.

ICT skills availability

There are wide gender differences in ICT skills and experience with certain tasks (with varying difficulty levels): for example, 17% more men than women reported they successfully installed or configured software recently. Another layer is the difference in ICT skills between urban and rural locations – a trend across the EU Member States – with those living in urban regions generally reporting higher ICT skills than those in rural areas. However, in many countries the differences in ICT skills between urban and rural locations are also wide, with inhabitants of urban regions generally reporting higher ICT skills.

Source: European Digital Skills & Jobs Platform